On the occasion of World Refugee Day, we devote an in-depth look at the work carried out by CIMA Research Foundation on displacement risk assessment. In particular, we discuss how it is possible to try to integrate socio-cultural and experience-related variables of people who have had to leave their homes due to natural disasters into these studies

June 20 marks the World Refugee Day, the international day established by the United Nations dedicated to all people forced to leave their homes and countries because of a “justifiable fear of persecution on account of race, religion, citizenship, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion,” as the 1951 Geneva Convention states.

We want to dedicate this day to some thoughts not only on refugees but, more broadly, on the different situations that can lead a person or a group of people having to involuntary leave their home, loved ones, work. We are talking about displaced or displaced persons, for whom we are carrying out activities aimed at reducing both the risk associated with displacement, favoring preventive ones (i.e., evacuations), and the risk that people, unable to move for various reasons, become trapped, without even the possibility of moving away from the danger.

If refugee persons have a well-defined legislative status, the one precisely made explicit by the Geneva Convention, which also guarantees their protection, for displaced persons the situation is different. In fact, the term applies to those who must leave, again for reasons beyond their control, their residence and often do not enjoy protections or support. Usually, most evacuees return to their previous place of residence within a short time, but in some cases the displacement may become permanent. The causes can be diverse, ranging from the presence of conflict to environmental disasters, such as floods or droughts; it is disasters that CIMA Research Foundation’s work focuses on. Thus, we can say that every refugee is also displaced or displaced, but not vice versa.

Broadening the view on vulnerability

To understand how to protect and support displaced people, the first step is to have a clear picture of the scale of the phenomenon. This is a complex step, however, because displacement can be arduous to track, especially in some regions of the world; in turn, this can make it difficult to allocate international funds to support these people. “However, there are some good international databases that can provide an overview of displacement. For example, CIMA Research Foundation collaborates with the International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), carring out a displacement risk assessment in Fiji and Vanuatu, island countries that are particularly vulnerable to climate change and extreme events, such as flooding,” says Eleonora Panizza, PhD student at the University of Genoa who does her research at CIMA Research Foundation. “IDMC provides a database that collects data from different organizations and institutions working in the field, allowing a picture of the situation in different areas of the world. This information can then be integrated, for example, with that available on UN-IOM’s Displacement Tracking Matrix and from the Humanitarian Data Exchange portal.”

These data can be the starting point for many activities to support displaced people and help focus efforts where they are most needed. They are also an important contribution to the work carried out by CIMA Research Foundation – work that is done mainly in a preventive view: our goal is, in fact, to provide displacement risk assessments or, in other words, to try to understand when, where and why the risk of people being forced to displace becomes higher. Our researchers focus, in particular, on flood risk, trying to refine the tools available to date, especially for vulnerability assessment. In fact, as we had previously reported, this type of analysis is currently based on the vulnerability of dwellings: simply put, a certain level of vulnerability is defined based on the probability of dwellings being rendered uninhabitable due to flooding. But, of course, we need much more in our lives: we need jobs, infrastructure, basic services such as schools and hospitals… The goal of our research group is therefore to integrate, increasingly, this component into risk assessment as well.

Adding “first-hand” information

Having available and being able to integrate all this information is not easy. In his work, however, Ms. Panizza takes it one step further still: to go and analyze not only data regarding damage to homes, crops or livestock, or even service facilities, but to turn directly to people. If they had to displace, at a certain time, why did they do it? How familiar are they with the risks in their own area? How many floods have they experienced in the past? There is a vast set of social, cultural, and economic characteristics that could help to understand how people would behave and what the dynamics of displacement would be in the event of a flood. This information could provide concrete input to guide policies and management strategies in the area.

“The goal of the work is to build an agent-based model, which, basing on information regarding the population of interest, can help us understand how different policies can influence people’s behavior and displacement risk,” Ms. Panizza says. “It is a type of model that allows for the inclusion of qualitative and heterogeneous data in the analysis. In our case, the aim is to simulate people’s behavior under different policy scenarios choices, trying to understand which ones are the most effective for managing the issue. We selected five of them, chosen on the basis of what emerged in a workshop conducted a few years ago in the IGAD region, where we collaborate on the Addressing Drivers and Facilitating Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration in the Contexts of Disasters and Climate Change in the IGAD Region programme, which was then just started: economical support for the population; awareness campaigns; support for reconstruction of damaged housing; the strategy known as build back better (in which the reconstruction phase becomes a moment to strengthen resilience); and activation of Early Warning systems. Within the model, we can vary the value assigned to each of these parameters, for example by considering a highly, partially, or poorly effective Early Warning system, simulating a number of false warnings or, conversely, unanticipated events. The outcome provided by the model is then returned in terms of the number of people displaced, evacuated (i.e., who preemptively left their homes), who remained at home, and, also, trapped people, i.e., those who did not have the opportunity, for various reasons, to leave.”

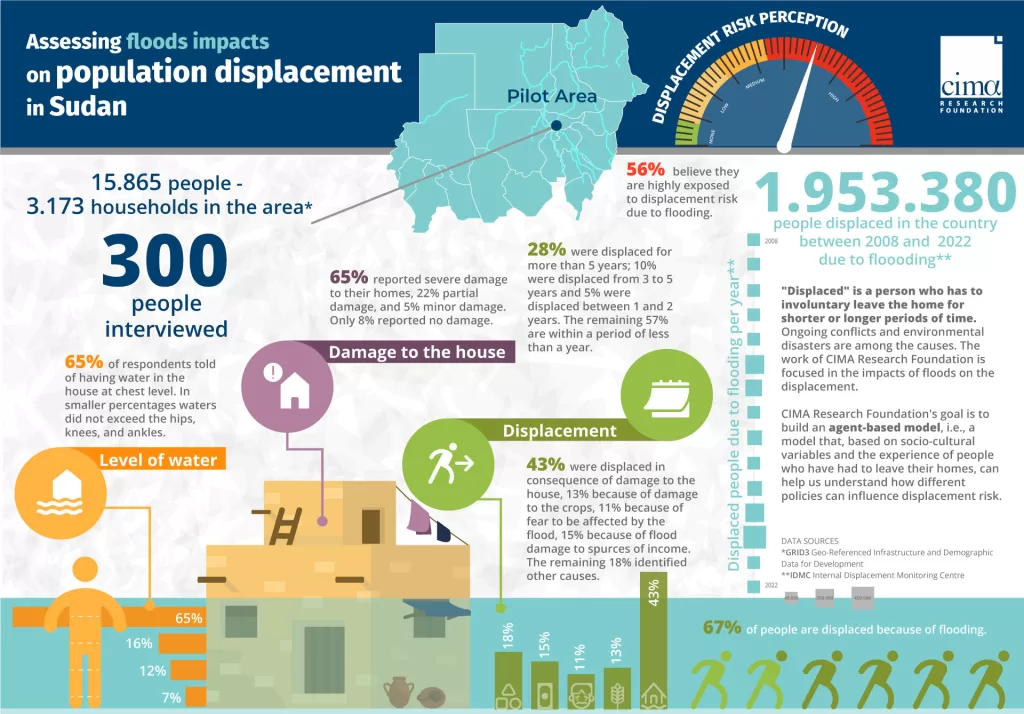

To build the model, Ms. Panizza, in collaboration with other researchers and with the support of Sudanese data collectors, gathered the necessary information, through questionnaires, directly from people in the area studied. She started from a small area, although theoretically and with the necessary resources the approach could be feasible on a larger scale as well: a small area north of Khartoum, Sudan, in which flood risk – and subsequent displacement – is high (CIMA Research Foundation is in fact also working in Sudan to strengthen drought and flood risk management).

Part of the work is still under analysis, and involves a series of semi-structured interviews with representatives of institutions and organizations to delve into the situation regarding flooding and displacement in the country and to discuss existing and desired risk management strategies. Data from questionnaires, however, have already been analyzed and part of the results was presented at the EGU General Assembly 2023, which brings together the academic world engaged in geosciences.

“This first part collects the results of questionnaires proposed to 300 people living in the area. These are valuable data to understand the perception of risk and the reasons for displacement,” Ms. Panizza further explains.

For example, about 43 percent of respondents who had to displace in the past did so because of damage to their homes, while comparable percentages, ranging from 13 to 18 percent, did so because of damage to crops or income, or even fear of the flood. In addition, only a small percentage of people displaced before the event: most moved away only when the flood was now in progress-an important element to take into account, both in assessing how helpful Early Warning systems could be and because we know that moving with a flood in progress implies a greater risk to people. Still, more than half of respondents report being fully aware that they are in an area of high flood risk.

“In general, this information provides a contribution to our understanding of the specific cultural and social characteristics of the context we focused on, allowing us to also broaden our gaze to include elements such as the perception of risk and the lived experiences of those who live there. On the other hand, when studying phenomena such as displacement, we cannot fail to take into account the ‘human variable,’ because our choices, including our displacements, are always the result of complex decisions that goes beyond, for example, the percentage of damage to the home,” Ms. Panizza concludes. “As complex as it may be to integrate these elements into risk assessment models, their contribution is certainly important. Remembering that our aim is not so much to limit displacement, which in some cases may indeed represent a form of adaptation, as to avoid forced displacement, which occurs in emergency situations – all the more so if we take into account that there are also those who have no way to move even in these cases. Reducing impediments to movement or increasing economic resources allows people who would need to move to do so without being trapped”.